Religious Groups within the city’s boundaries – There would be many!

Before the arrival of wave upon wave of immigrant, factory workers into the Merrimack River Valley township, which, later, became Lowell, only Yankee resident farmers could be found in the craggy fields and granite-strewn, verdant landscape upon which the future, massive, red-brick, manufacturing denizens of the America’s Industrial Revolution would flourish and prosper.

During these early years of the American nation, before 1830, civic leadership and socioeconomic progress were maintained by former colonialists whose ethnic lineage had emerged, mostly, from their British ancestry. And, as a result, a Presbyterian, Unitarian, Calvinist and Anglican social mindset prevailed. These intrepid, early citizens had adopted a challenging lifestyle marked by long, harsh winters, poor land to cultivate, native forests for timber and ship building and, of course, harbors to develop for trans-Atlantic trade with Europe.

Native tribes that had previously roamed these territories as hunter gathers and traders no longer held any sway over how the local rivers, lakes and streams plus the surrounding fields and hills would be managed. For these indigenous tribes of the region, the developing European manners and viewpoints must have seemed as the onset of a complete reversal of their time-honored way of life.

It is not clear how our European ancestors managed to incorporate this harsh social reality into a just, Protestant ethic of the period. Religious leaders like John Calvin, Martin Luther, Menno Simons and John Wesley may not have had, yet, successfully moldered the minds of their followers to the post-Reformation thinking after centuries of religious wars. How to deal with indigenous peoples was not a question foremost in the minds of these reformers.

From a theological viewpoint, the native people were not persons on an equal, human footing with Europeans, but often human candidates to be converted to a European brand of attitudes and beliefs.

As a young student in a Franco-American, elementary school, some 350 years later, it had never occurred to me to ask, “Were the Native-American peoples treated fairly by their more powerful European overlords?” That simple question had never even been addressed in any of my many American history classes. Yet, other classmates and I simply accepted the answers proffered by all adults in our world, i.e., “These savages would greatly benefit in all ways by simply accepting a faith conversion to one of several Western-European religions.”

Open discussions on these complex, theological questions were seldom or ever philosophical issues, which might be worth even a brief column on page 2 of the Lowell Sun’s Sunday edition.

However, it would be totally incorrect to suppose that the very “Cradle of the American Industrial Revolution” lacked any deep religious fever, enthusiasm and diversity during the first half of the 20th Century when my grandparents plus aunts, uncles, cousins and parents roamed the quaint cobblestone streets of the city.

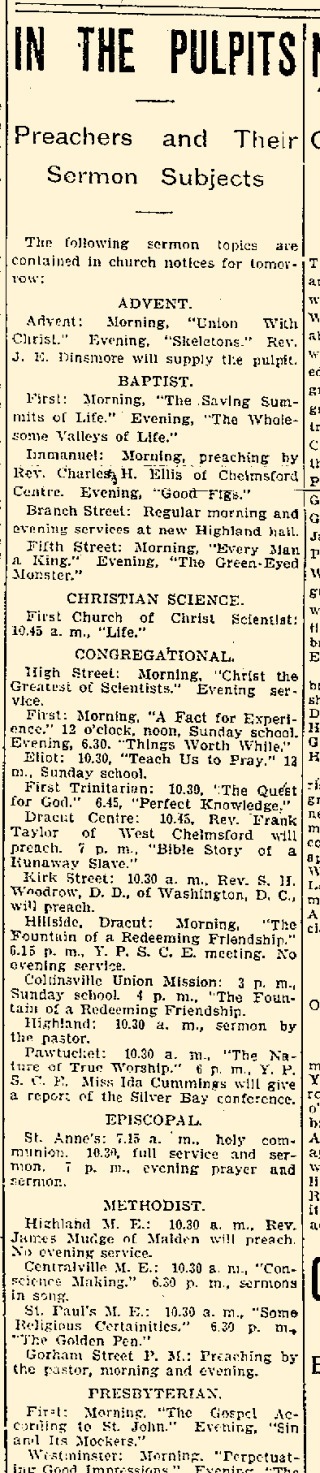

In contrast, few New England towns could boast of a broader variety of diverse believers than that found within the city’s confines. The attached Lowell Sun column is given as evidence to substantiate this claim.

It is clear that the Methodists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, plus the Congregationalists, Christian Scientists, Baptists and Adventists all had a meeting house of their own to formulate a worldview that happened to be centered in this town nestled in the busy confines of the Merrimack River Valley.