Careers, Professions and Jobs in the City

Opportunities to experience a more rich and rewarding lifestyle for the first and second-generation immigrant groups in the city’s scattered ghetto neighborhoods remained an everlasting glimmer of hope post the horrors of the First World War, the Spanish Flu Epidemic, and the slow decay of the massive mills producing textile and leather goods.

This disheartening period of hand-to-mouth, industrial existence for workers housed in sub-standard, three-story-tall, wooden tenement buildings often further tested the resilience of the brave but nearly destitute cadre of Irish, Greek, French-Canadian, Polish, Portuguese and Russian-Jewish inhabitants of our Spindle City on the Merrimack River.

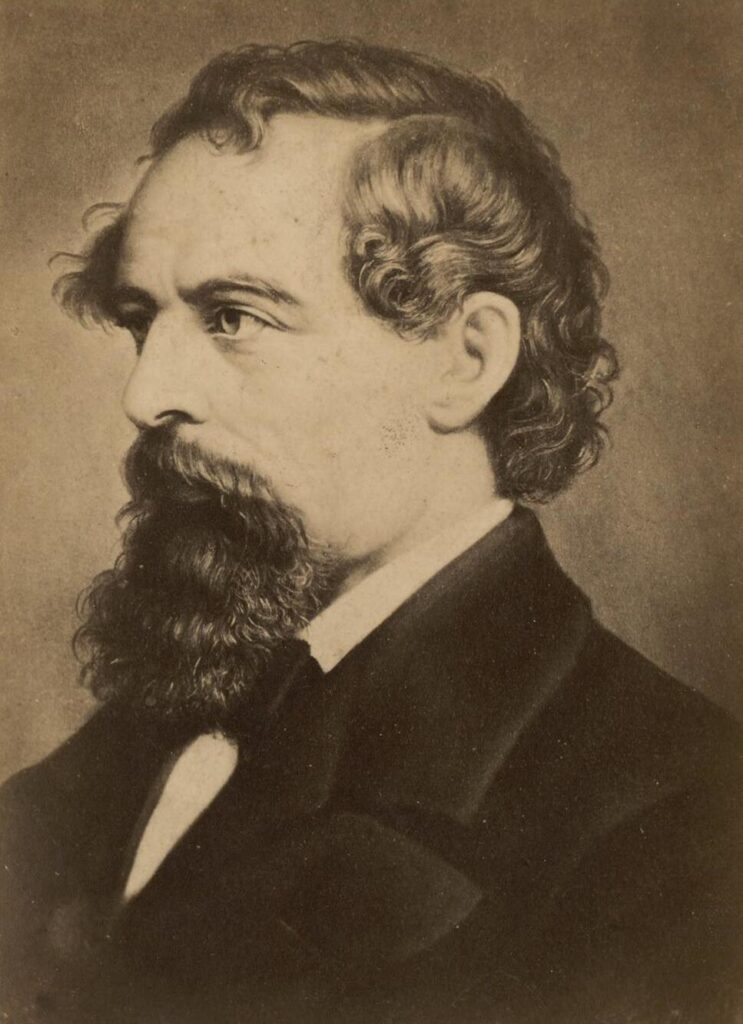

Times were tough even when the city initially obtained the attention of Charles Dickens during a visit he made to the city around 1842 as he compared the town’s canals, working quarters, and tenement living arrangements to those he had described in several novels about life in the working, London slums of his youth. For Dickens, working-class, industrial poverty evoked a feeling of being back home.

Big Questions

Is it possible to fashion a wholesome, family environment with a bright future for the children, who were then living in dilapidated tenements without trees and grass and breathing the smokey emissions from those huge smokestacks? Questions like these must-have psychologically discouraged mothers and fathers plus the many youngsters (ages 9 or 10) assigned to dangerous jobs within the daunting, factory walls.

Looking Over the Horizon – XXX

Similar doubts must have upset my mother and father plus all the long retinue of French-Canadian aunts, uncles, and cousins, who were part of the town’s working stiffs during the dismal period after the Depression and World War II. Of course, all the other minorities scattered across the city’s ethnic neighborhoods, virtual ghettos, of the industrial landscape also experienced similar feelings of isolation, fear, dislocation, and hopelessness.

Life in the city that housed eleven, competing textile manufacturing behemoths, each four or five stories tall, must have seemed daunting for the inhabitants, who usually arrived in town with few personal skills and aptitudes required in large-scale industrial manufacturing. These massive, red-brick factory buildings – often, a football field in size – would become the lifelong workplace of an Irish gal from Limerick, an energetic lad from Athens, or a hopeful Canadienne-francaise from Montreal. Similar scenarios were played out by other arrivals from Portugal, Poland, Romania, and Russia. The town had become a virtual international center of linguistic and cultural connections, a united nation of the lost and destitute.

This is the world that all immigrants to the city would hopefully learn to navigate. My relatives, going back to grandparents in the 1890s, were proud participants in this socioeconomic diaspora.

“Help Wanted” ads dotted the classified pages of the city’s major newspaper, The Lowell Sun, inviting locals to fill empty slots in the intricate and interlocking machinery of industry. Immigrants could, eventually, be introduced into the existing city life, but, first of all, they needed a job, even a low-skill, poorly paid job, to get started.

My relatives going back to the days of my great-grandparents (1865 -1890) perused the classified ads for this newspaper in an effort to reach new levels of well-being through gainful employment.

In the next section called: “Lowell Sun classifieds”, a broad range of career opportunities for the 1920-2000 time frame are presented for a quick overview of the jobs’ situation.

Of course, no single person hoping to find guidance in selecting his/her ideal field of interest had such data available before the advent of optical character recognition, OCR, and relational databases, Such analytical tools are now available and could be used in making career choices.