Since I was born in January, 1939, my personal experience regarding the Great Depression is fragmentary, at best. However, the years surrounding home-front, domestic events during World War II, left me with an indelible appreciation for the resilient guts and determination shown by Lowell’s impoverished immigrants of every ethnic and cultural persuasion. Curiously, the daily travails, fears and uncertainties of this mostly unskilled, under-educated and poorly trained layer of industrial society had hardly changed since the ear-shattering Wall Street crash of 1929. There was little reason to expect that the halcyon days of Lowell’s pre-World War One economy might return even if the clanging of a new war could be heard across the Atlantic and also in the Pacific.

Conversations that I overheard all around me either while napping in my crib or while relaxing over a bowl of pablum in my high chair in the kitchen were often focused on maddening events happening elsewhere like in Oklahoma, Maine, Washington, Chicago, Boston, etc. but also in Tokyo and Berlin. To me, it sounded like a nonstop mishmash of problems lasting decades. Many people in the U.S. and in Europe were apparently upset about not finding work, the high cost of butter and settling for margarine, the dust bowl, Prohibition, the mobs, market volatility on Wall Street plus Hitler’s actions in Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1938 followed by Poland in 1939. Finally, to top it off, Pearl Harbor really shuck us up in December, 1941.

Looking on the positive side, though, a few more local people were employed making combat boots, knapsacks, gas masks, tents, parachutes and bullets for the Army and Navy in preparation for the war to come and, later, for the war that was. It seems to be tragically true that disasters seem also to open up new avenues for a creative population to make the best of an ugly surprise. In this sense, the typical human being on our planet is a walking, talking panorama of potential solutions.

As a young person with strong family ties to a Quebec-based, 17th Century, French Catholicism under the guidance of the Pope in Rome and my pastor (mon curé de paroisse) at the Église Saint-Louis de France in Lowell, Massachusetts, my allegiances were already divided among several, historical viewpoints. Franco-American, textile mill laborers carrying these insignia, generally, considered themselves as hard-working Republicans, whereas similar, Irish, immigrant families often tended to side with the local Democratic attitudes and issues. In contrast, workers from a Greek, Polish, Portuguese, Lithuanian, etc. backgrounds may have divided their political allegiances equally across Republican and Democratic ballots. I simply did not know.

Summary of Grievances: No butter, again, so we used margarine; Roosevelt is a terrible President; farmers out west were slaughtering many, many pigs and letting the meat rot in the fields while some people, even in Lowell, were going without meat because there was no work in the factories. Everywhere, you turned, the whole system was broken, kaput, and Democrats everywhere were responsible! Of course, we were hard-working, poorly paid Republicans so it just was not fair!

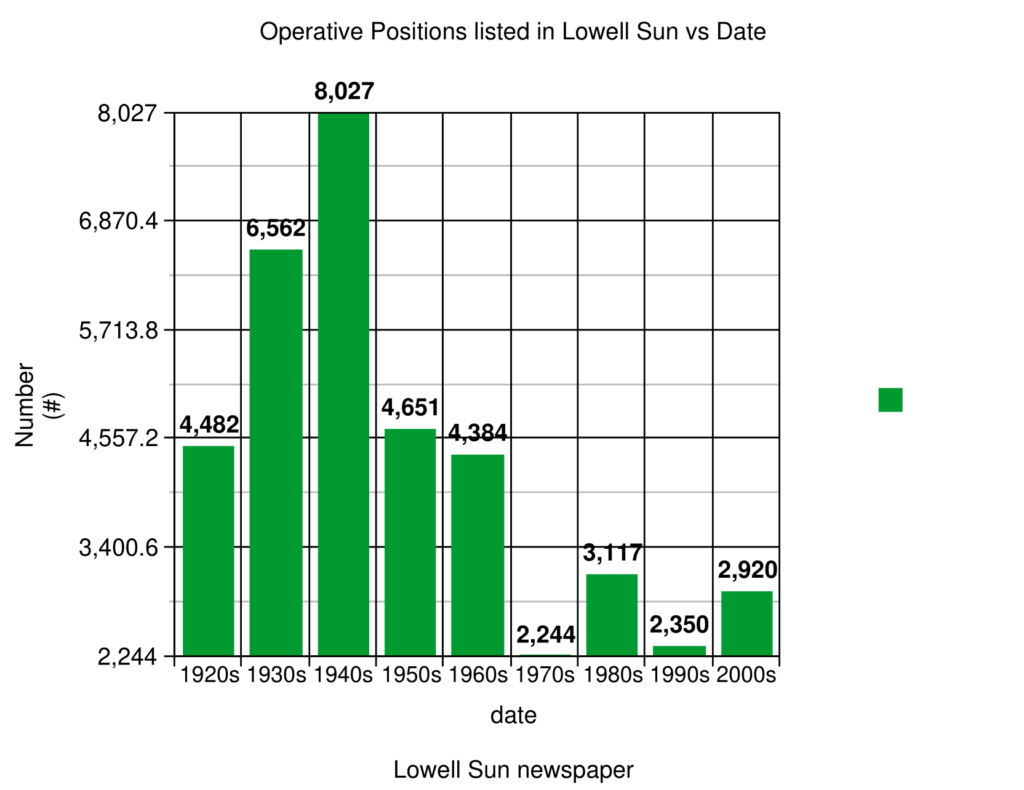

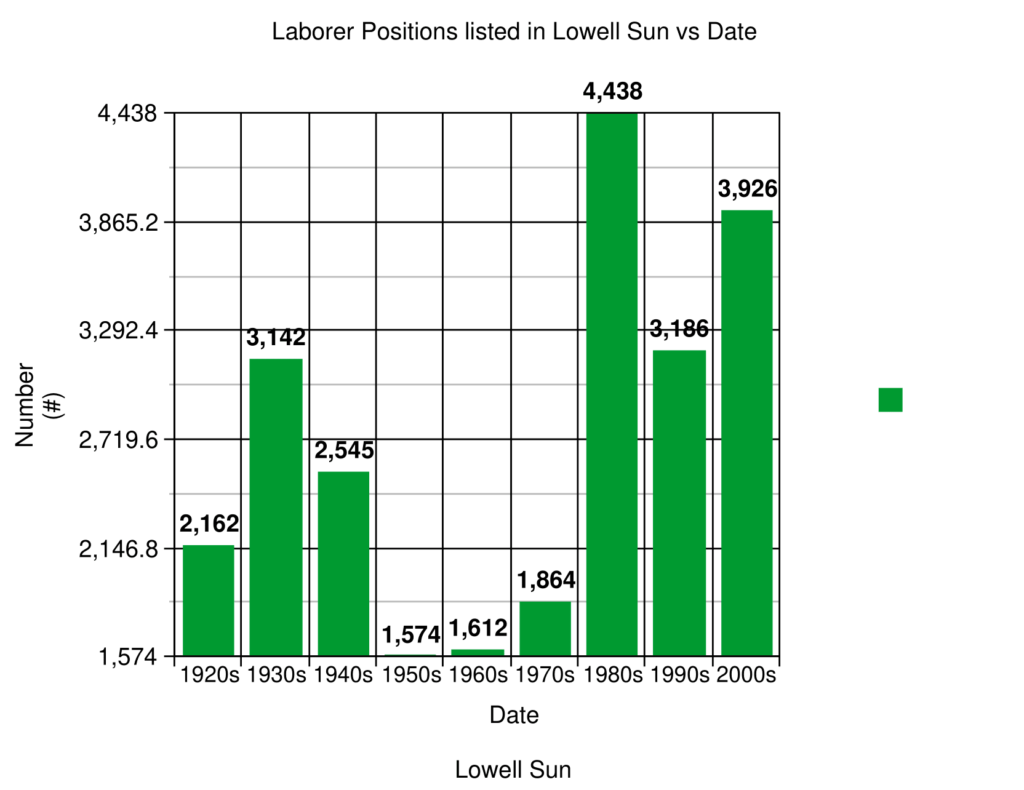

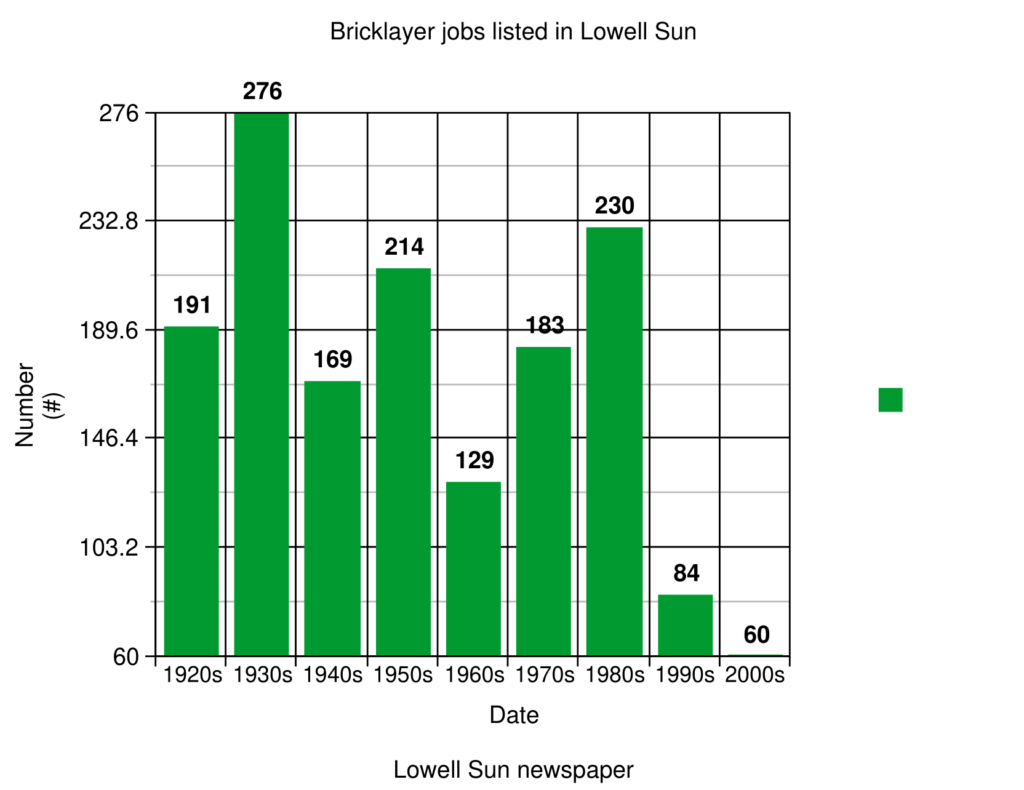

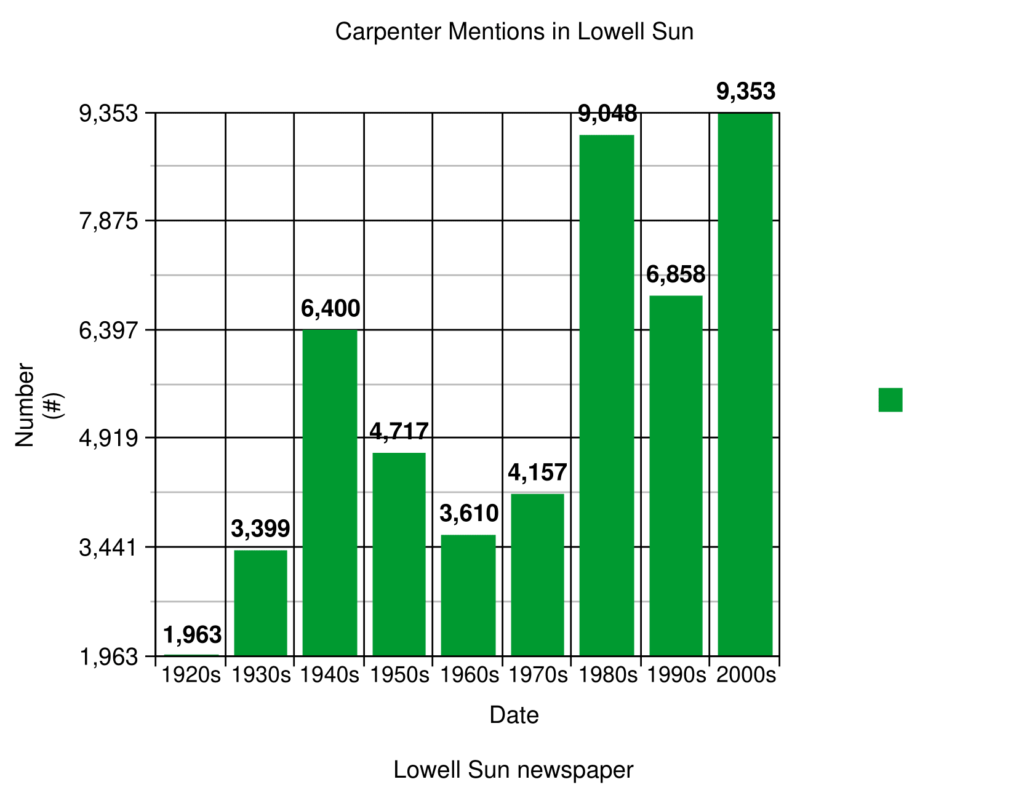

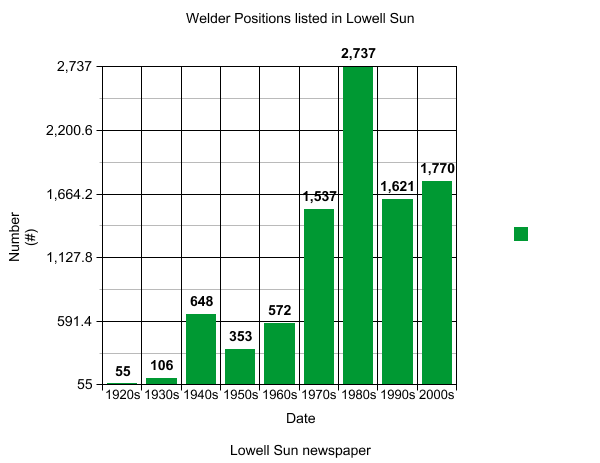

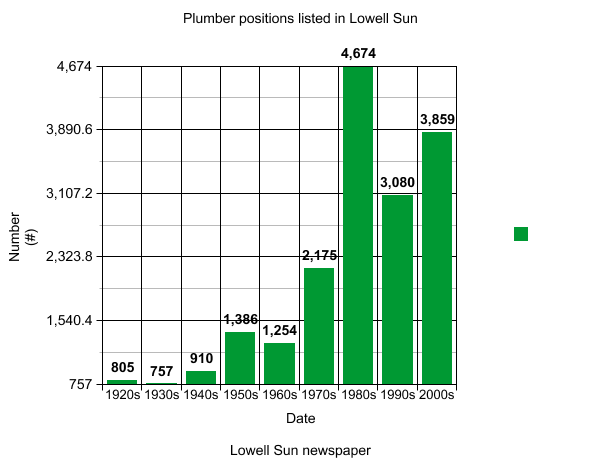

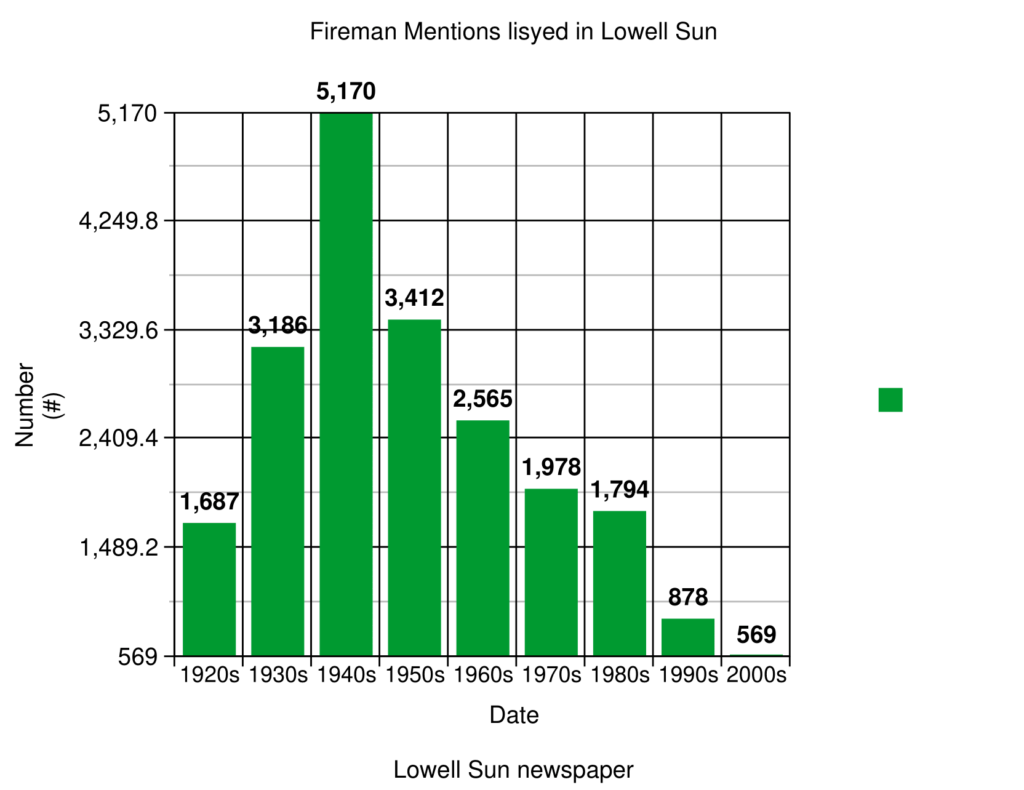

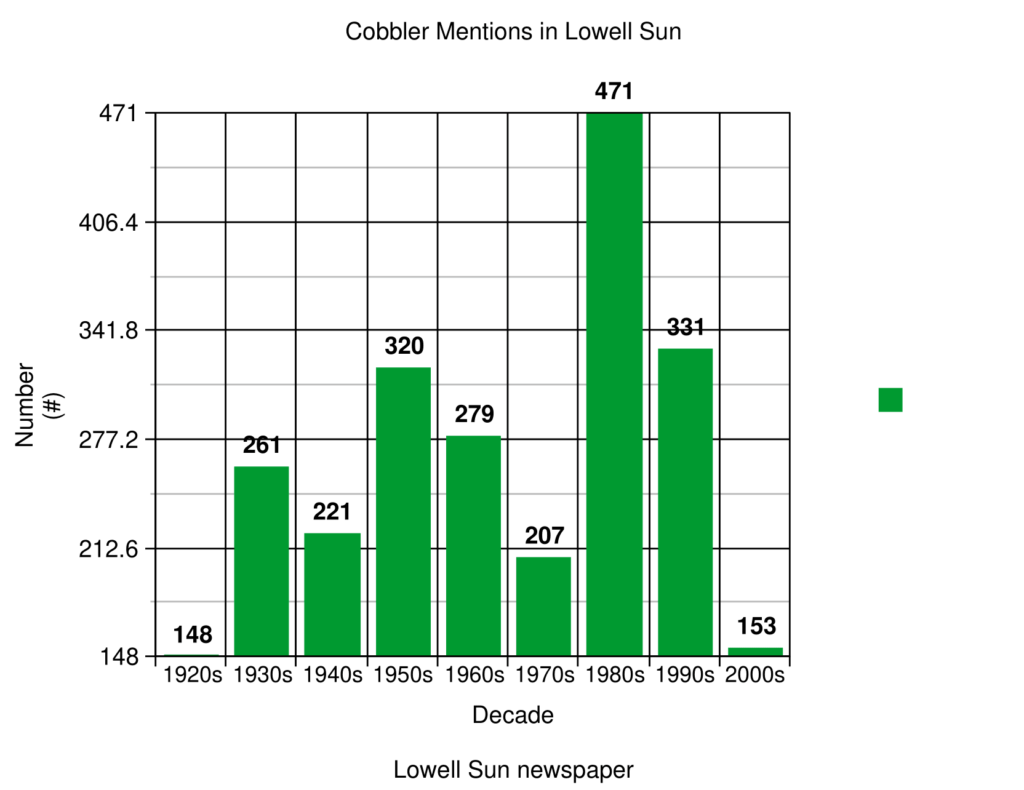

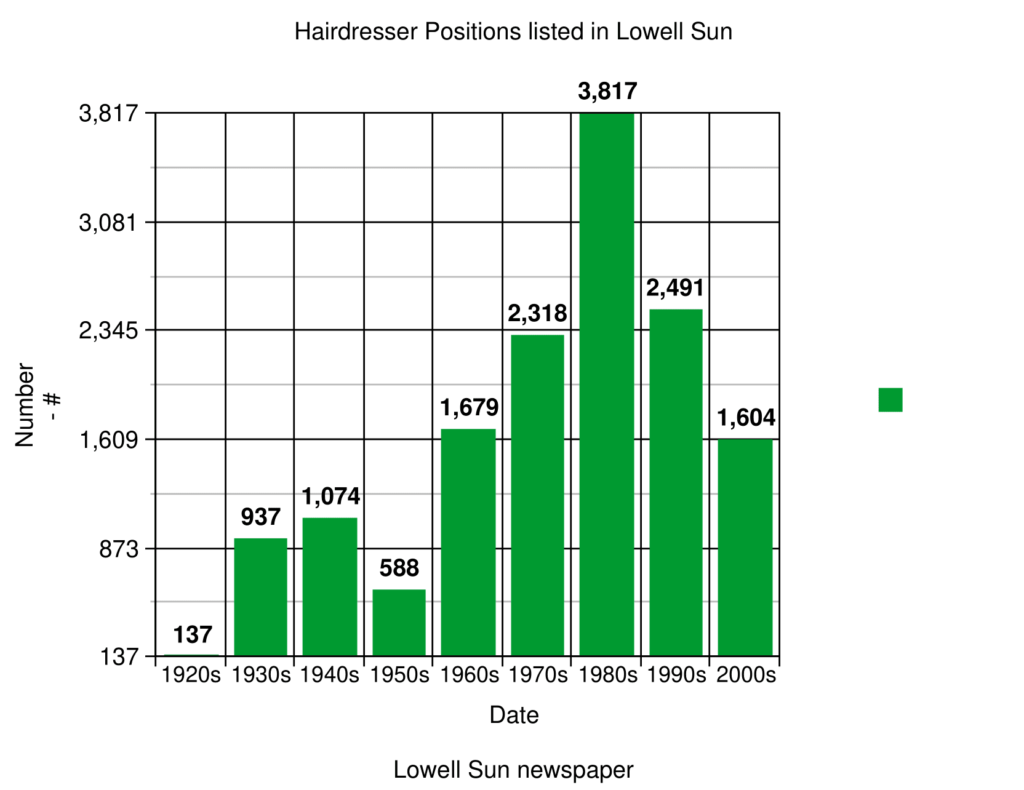

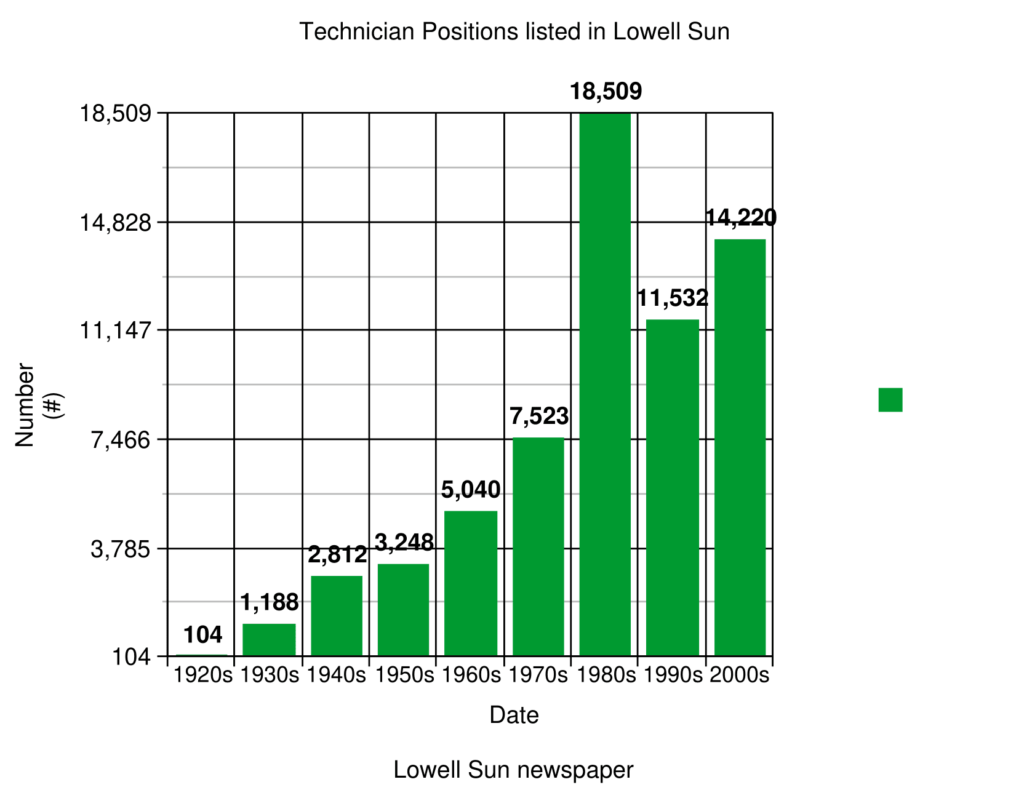

Below, I have included statistical data showing the number of times per decade our local newspaper, the Lowell Sun, mentioned key job categories such as: operative, laborer, bricklayer, etc. In this way, the reader can obtain a quick overview of employment conditions from 1920 through 2000. People with certain skills managed to survive the Depression years better than others.

Laborers did not do well in the 1950s and 1960s, but a person could still have a job as a laborer even at the peak of the Depression (~ 1934). Curiously, there was plenty of work for such a worker between 1980 through 2000.

That ancient craft of the bricklayer (see below) showed a remarkable resilience over the years from 1920 through the 1980s. It is curious that the years of the 1990s through 2000s seemed so lean.

Note: In the 1920s and 1930s, several mill owners decided to make some repairs to the aging, monstrous, football-field-size factories within the city. This decision would be good news for all bricklayers in the region since nearly all existing textile factories used a brick exterior facade.

Carpenters are always on call when new home building is the rage. Also, a massive national effort during WWII in the 1940s heightened the job opportunities for this class of labor.

JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ

LLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLLlll

YYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY

RRRRRRRRRRRRRRRRR

Although my mother had a high school degree from the College Saint-Louis in Centralville, she never used her education in a local, downtown clerical position. After her years of delivering milk to homes and businesses in the area and trying her hand in nursing (no details available) and opening a hairdresser’s shop in Lowell, her role as a homemaker dominated her hours as a mother, wife and caretaker for our paternal Memere.

I bring this out here since her skills as a hairdresser became a source of additional revenuue to maintain our family finances above the critical water line, which maked my daily existence and that of my parents plus my brother and two sisters over the long years of near-poverty. The mention of hairdresser for the 1950s shows a nearly 50% decrease from the number of 1074 of the previous decade. Since my father died in January, 1953, our depending of a suffiient stream of income from my mom’s home business at tht time would hame been the height of folly. True, my brother and I could each clear $3.50 per week from our newsboy businesses, but in 1953 our cupbords were running short on vitals. Dreams of long-term well-being seemed fancyful, at best. Maybe, even foolish. Although I did not know this French proverb at the time, “La vie ne fait pas de cadeaux.” Loosely translated, one might say that “Life makes no gifts” or “Life means tough sledding.”

SSSSSSSSSSSSSS

UUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUUU