Many years after leaving Lowell in September, 1963, and equipped with many personal, human interest stories coming from the mouths of friends and colleagues that I had encountered in other Massachusetts towns plus those in Pennsylvania, California, Brooklyn, France, Berlin, Munich and Albuquerque, I began to ask myself, again, how had I been fashioned or molded as a product of this post-industrial textile giant.

What lasting impressions had clearly been stamped upon my brain cells through my total immersion in Lowell’s working-class, immigrant mind set?

How had I perceived, over the many interloping years, my own early experiences while living with numerous, Franco-American relatives in the city from 1939 to 1963? What were the positive results and, also, what were the negative, or less helpful, attributes of this background?

Impressions, Attributes, Viewpoints, Prejudices – Local Culture, etc.

How does anyone become a typical Lowellian, who experienced the widely changing times during that interesting time period of 1939 to 1963? Those were personally my most interesting years of growth and adaptation just before WWII and during the early years of the Cold War.

So, for me, my response would have been loaded with a few, modest, academic achievements plus many social, economic and emotional forays into the lives of important others. Finally, these experiences were all neatly packaged into a healthy mix of happiness, discovery, surprise, childhood disappointments and a few quite painful losses. Even after my nine years of elementary school at l’Ecole Saint-Louis de France, my tiny brain was already forming a worldview, which was loaded with the unexpected, the eye-opening surprise coupled to a growing, internal sense that everything “out there” was tentative, at best. Seldom did I feel A-OK in an A-OK world. Where was that sense of safety and stability, which the kids on “Father Knows Best” enjoyed everyday?

Mother and Relatives Probably Knew Best

Our kitchen area was often the neighborhood gathering hall with aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents and friends. Of course, the main reason for our recognized, local popularity at the corner of Ludlam and Dana rested squarely on my mother’s broad shoulders and her inviting smile. She simply oozed with gracious hospitality. “Come on in and have a piece of fresh strawberry pie.” Her words still ring clearly in my mind.

It was in this central hubbub of our tenement kitchen that local truth was often recounted, again and again, by working-class people, who had personally experienced the Spanish Flu, the Roaring Twenties, the Wall Street disaster and the ten years of economic and emotional Depression that followed. Then, they also had had the chance to live through World War 2. Some of these folks could actually recall the days of Woodrow Wilson and Lowell highlights in the early 1910s when 60-hour work weeks were available for the physically strong immigrants, who were still pouring into the city.

Kitchen Table Topics

- Red Sox better than the Yankees – No, Yankees better than the Red Sox

- General Motors (GM) – Buick is the best – Bob Bolduc

- GM is a going concern- My brother, Bob

- Ted Williams better than Joe DiMaggio – Paul Bolduc

- “Ted Williams, he’s a bum!” – Uncle Gerry’s thoughts

- Birth control – l’empêchement de la famille – wrong and a sin – Everyone

- The Democrats in government – “Crooks! all of them!”

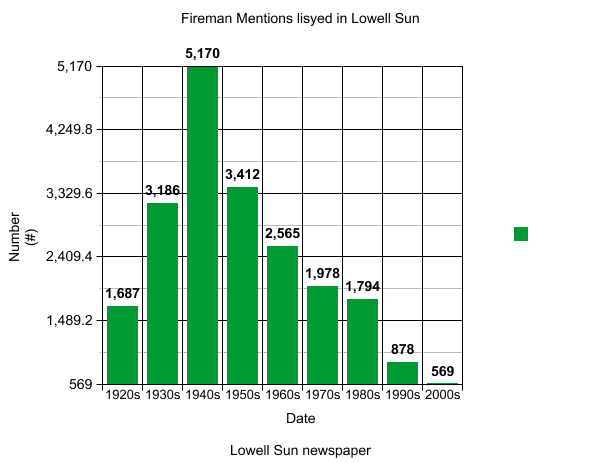

- Firemen in the city got those jobs through favoritism & political corruption.

- “Hurricane of 38: the worst of them all with all that flooding in the city.”

- The Bolducs in Pawtucketville think that their shit doesn’t stink.

- Irish women can’t cook as well as our canadiennes-francaises.

- Best cowboy in the movies? Gene Autry or Roy Rogers? – Bob and me

- Times were tougher during the Depression than during WWII

- Monsieur Pinard was the saint in our world. – All agree.

- Danger: “Don’t walk at night in the Greek parts of town.”

- “President Truman is a crude little man.” – My Mom’s comment.

- “Abortion is a mortal sin – un péché mortel” – All agree.

- “Fermes la porte. On ne vit pas dans une grange.” – Mom to the kids

- “President Eisenhower will protect us from those Russian A-bombs.”

- “Evolution is wrong! We don’t come from monkeys.” – All agree.

- Premarital sex is a sin. End of story! – All agree.

- It’s a dog-eat-dog world. Stay alert! – General agreement

- “He is a snake in the grass.” Beware! He is someone you can’t trust.

- For Lent, you need to give up a pleasure that you really enjoy.

- Life sucks and then you die. – Some agreement

- Life is like shoveling shit against the tide. – Everyone agrees

- Life is not always a sunny day at the beach. – General agreement.

- “In the mills, managers would spit on us as we walked down the spiral staircase.” – Aunt Florence

- “You are lucky, Claire. You never had to work in the mills.” – Florence to my mother.

- “You win some and you lose some.” – All in agreement

It was with this residential sack of accepted pearls of wisdom, that I set out on my personal quest for meaning and goals in our troubled world of ideological, political and religious misgivings. Could a guy with a fervent set of Lowell teachings under his belt manage well in a wide, wide world of non-Catholic, non-Franco-Canadian believers, who still clung onto their ethnic, linguistic and religious traditions going back to the late Middle Ages of the 1750s? That was the challenge.

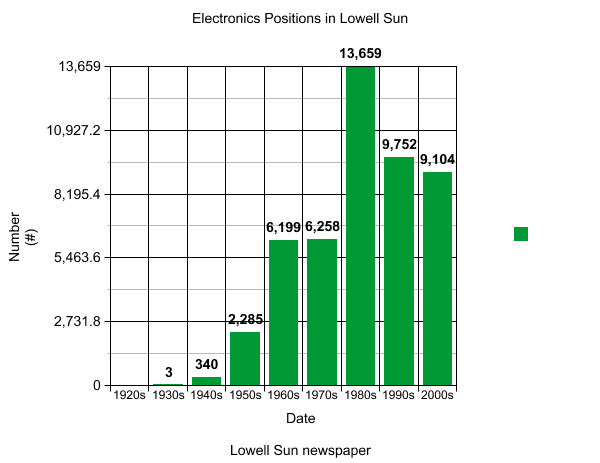

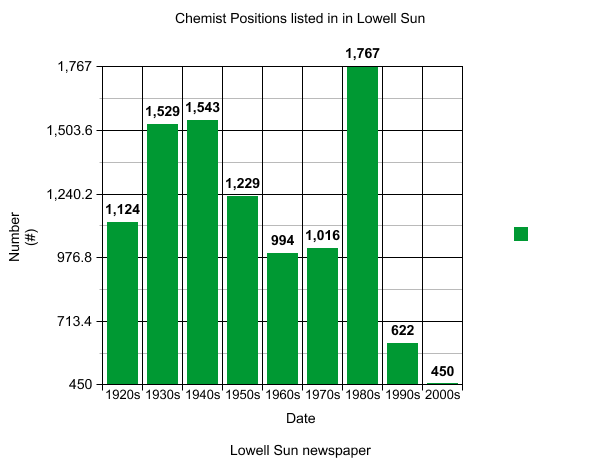

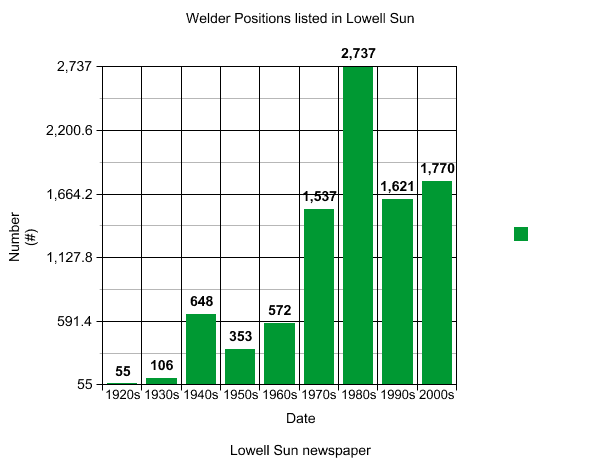

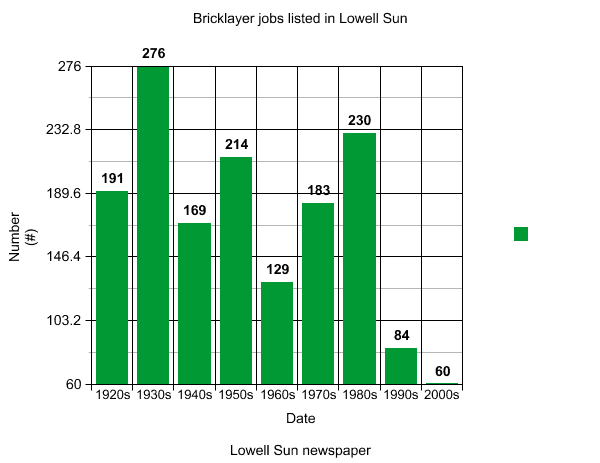

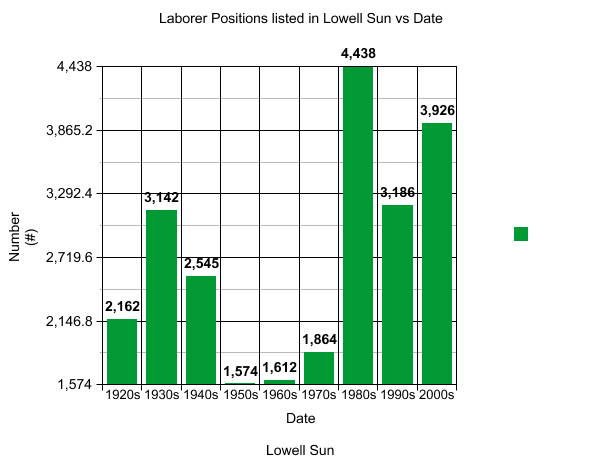

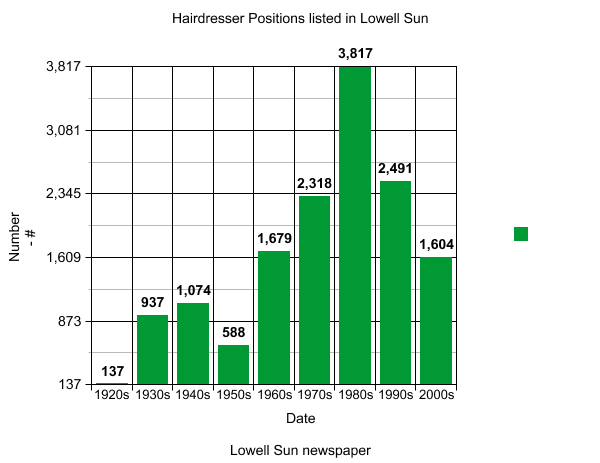

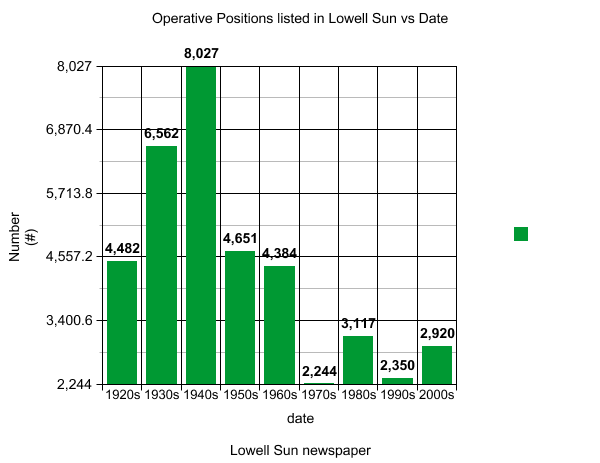

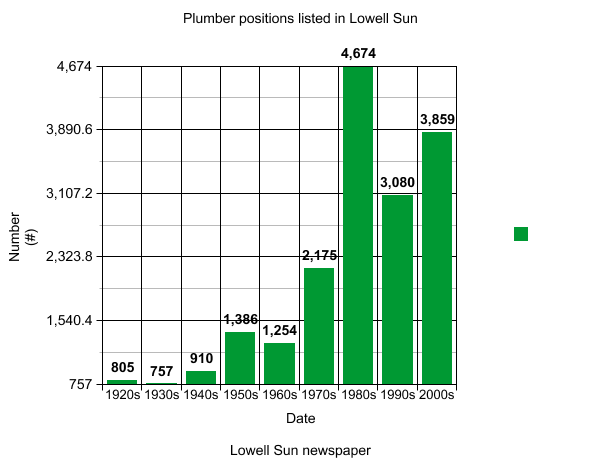

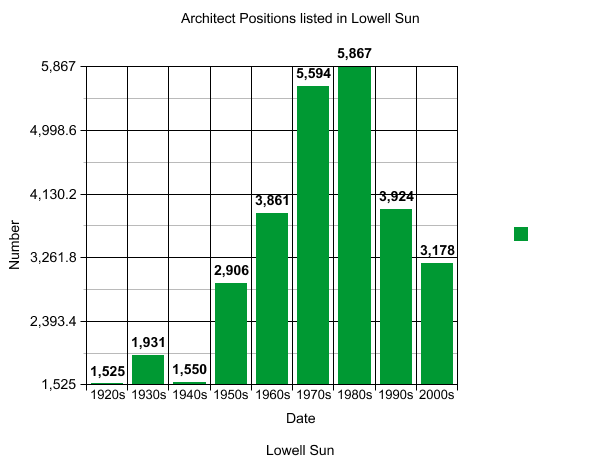

In trying to answer this question, I was first interested in knowing how the various immigrant groups had fared job-wise in the city during the decades before my arrival on the scene. What were the employment pages of the Lowell Sun saying about the jobs/work situation plus the exciting new career opportunities then available in the city over the years?

After the advent of optical character recognition, OCR, a digital advance that made access to old newspaper copies possible, any researcher could look into the details of the job market in any locality in the USA over the previous decades. This is the information that I found very useful in better understanding the work-a-day world of life in my hometown.

The job categories of people whom I knew personally or indirectly fell into classes such as: laborer, hair dresser, operative, taxi driver, plumber, nurse, teacher, cobbler, fireman, bricklayer, etc. Other classes like biochemist, scientist, technician, contractor, lawyer, biologist and more were also occasionally mentioned but these people were, generally speaking, outside our immediate set of contacts.

Given below, the reader will find a time correlation display of job opportunities open to some familiar classes in the city.

The listing above covers work categories that were actually filled by people that we personally encountered in our daily dealings in Centralville, Dracut, Pawtucketville, Tewksbury, Tynnsboro, the Acre and elsewhere in the city. Other classes of workers also made important contributions to the local economy, but, generally speaking, these individuals were especially trained in a career fashion to reach a higher status of recognition. In contrast, their corresponding job classifications are given below as typical examples.